Interviews

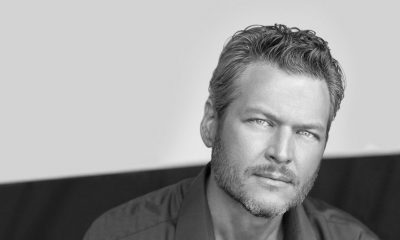

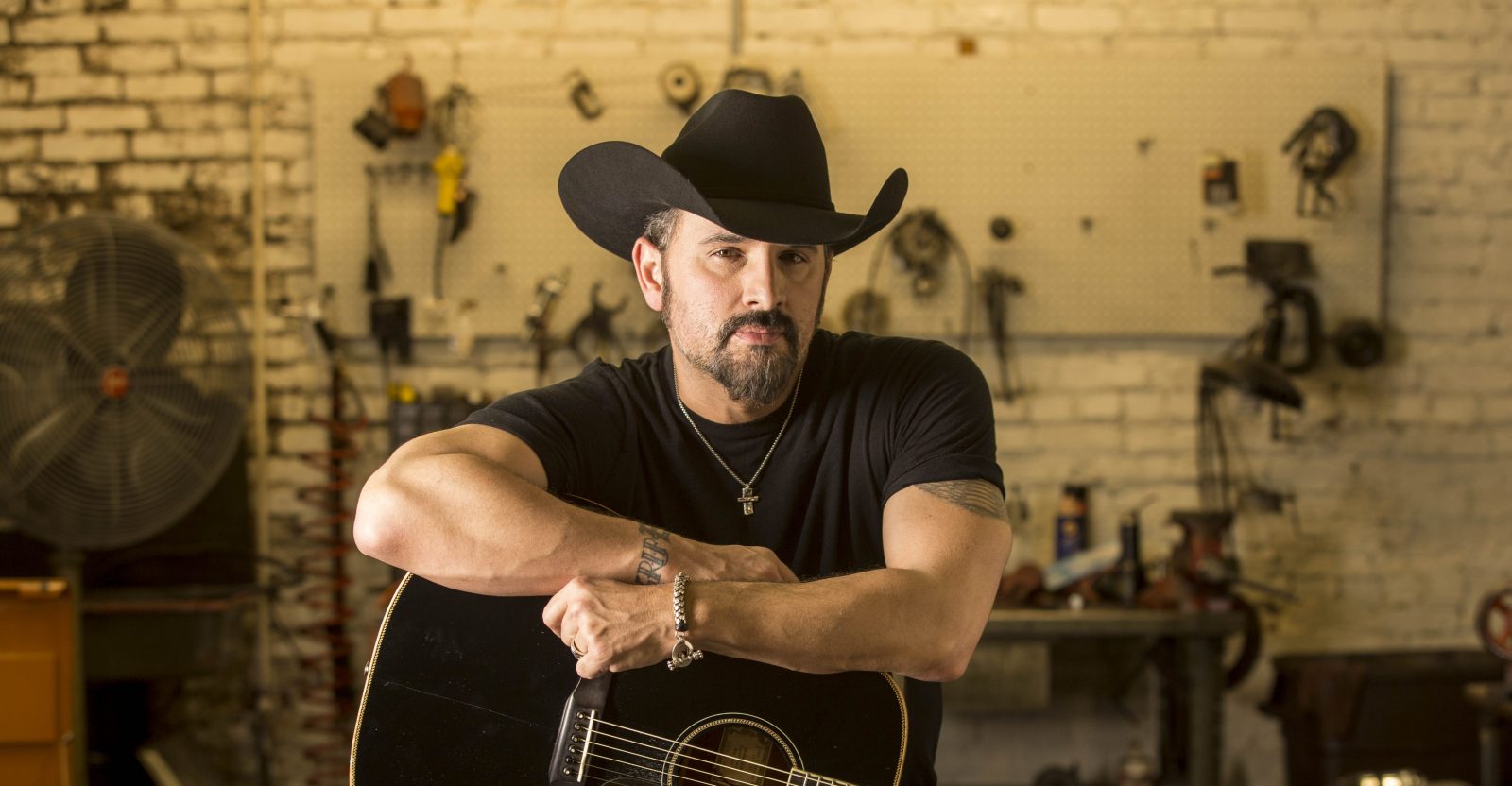

Ray Scott Finds Creative Freedom In Life After Warner Bros.

Ray Scott thought he had done pretty well for Warner Bros. After all, the husky-voiced baritone from Semora, North Carolina, managed to sell over 100,000 copies of his 2005 debut album, My Kind Of Music, despite the fact that his music received virtually zero airplay from country radio.

Sure, the record wasn’t a grand slam, but it wasn’t exactly a strike out, either—not with numbers like that. And not considering the outpouring of critical praise it received. (Billboard was among the list of publications to name My Kind Of Music one of the top ten country albums of the year.)

Certainly the album performed well enough to warrant a follow-up. Maybe his career path wouldn’t lead him immediately to super-stardom, but Scott thought, when all was said and done, that he had successfully built a foundation which his sophomore effort could stand on. And he was willing to make a career the old fashioned way–with a whole lot of hard work.

But in the high-priced world of major label music, 100,000 units is a drop in the bucket, and what Scott saw as a sign of commercial strength, was, in the eyes of Warner Bros., a significant commercial failure.

“They wanna strike gold and sell millions of records right off the bat,” Scott says. “They want to get the stuff that’s the most vanilla and most dumbed down. They get excited about something that’s different and original, and then give up on it if it doesn’t blow up big out of the box.”

Scott’s second album was green-lit, of course. But it was a time of turmoil at Warner Bros., and although the project was moving forward, its pace was a trudge, and it kept getting stalled. “Summer becomes fall, and fall becomes the first quarter of next year. I got really disenchanted,” he says, about the lack of action and motivation at the label.

“If you hire a guy to be a leader, the dude needs to have opinions and move on them,” Scott says, speaking about Warner Bros. Nashville head Bill Bennett. “And he just never did. He was always passing the buck. To see the indecisiveness and the lack of order and organization that was underneath that roof. They would tie up people and just let their careers sit and rot.”

What affected Scott and his music even more directly, however, was the departure of A&R head Paul Worley, who was replaced by Scott Hendricks in 2007. Hendricks stepped in and “cleaned house”–a fact which resulted in Scott being assigned an entirely new A&R staff–halfway through the process of making the album.

And his creative control was reeled in considerably. “Basically, I was in there fighting them on everything. They were so afraid of radio and what radio would play. They wanted me to cut a song from a proven songwriter. They wouldn’t come out and say it.”

“My experience was not unlike Joanna Cotten,” he says. “Here they have a unique artist that they make all these promises to, and at the end of the day they’re too scared to do anything because they’ve already got it in their minds that they’re going to fail. I finally told Hendricks, if this ain’t feelin’ right, it ain’t gonna hurt my feelings. Let me go and do something with this stuff. It was more or less his decision. It was just a good move. There was no way it was going to work at that point.”

By that time, Scott had nearly completed recording that second album for Warner Bros. But once he had been officially cut loose by the label, which retained ownership to the recordings it had financed, the only way to release that album to the public would have been to pay Warner Bros. on a per-unit basis.

And the singer, who holds a college degree in Music Business studies, had already come up with a more financially promising idea.

Scott brought together a select group of trusted colleagues and recorded a second second album, which he released on his own label, Jethropolitan. Instead of paying Warner Bros. for the work he had already completed, Scott kept the recording costs for his new project low–even going so far as recording one song in a bedroom–a fact which would allow him to start turning a profit at a much lower sales threshold. “You can go make eight bucks for every record you sell right off the bat, as opposed to having to sell 400,000 before breaking even.”

“By the time I finally got off the label, it was ‘God, thank you.’ I told my manager, ‘I guarantee that you’ll never meet another artist as happy as I am to be getting dropped.’ I knew it might be tough to get another major label deal. But I also knew that a lot of these labels are signing artists to 360 deals. They’re taking this approach to try to justify the money they’re laying out for these people’s careers, but the deals these new artists are signing are ridiculous. If you thought we were getting raped before, it’s really bad now.”

Even so, Scott says, it was never about the money. Armed with complete creative control, he was able to make the record he had wanted to make in the first place–a record steeped in the musical traditions he was raised with, brimming with the stories he–not a group of label executives–wanted to tell. In fact, many of the songs on Crazy Like Me were in the running to appear on My Kind Of Music but were, for whatever reason, nixed by A&R.

The result of that new-found freedom is an album that is considerably more colorful than its predecessor.

“This time around, with me calling the shots, I included a few songs on the album that they wouldn’t have wanted me to record. “Ashtray On A Motorcycle,” was one of those. When we were picking songs for the first album, I played that song for the A&R staff and they looked at me like I was crazy. I don’t know why they were afraid of some of this stuff. I don’t know if they were scared of offending people, or that it wouldn’t appeal to women, or the language, or what.”

Scott doesn’t think his music justifies any of those fears. In fact, the oft-cited torchbearer of so-called “outlaw country” doesn’t even think his music is that far outside the mainstream. Some of his fans are fans of Rascal Flatts, too, he says.

“I’m not trying to make something that sounds like Bob Wills. But it’s a little more reminiscent of what I grew up with.”

Still, Scott is ready for the harsh reality of life as an independent artist. Any success he will find with Crazy Like Me will be the product of his own hard work. And just like last time, there will be little radio support. He knows all of that. So this time, he’ll focus on utilizing a grassroots approach to promoting the record, and he’ll turn to the more cost-effective arena of digital distribution. And he’ll stick to winning over new fans in a time-tested way–by pounding the pavement and bringing the music to the people.

And although his new independent career may never be able to launch him to the heights of stardom that a major label artist can hope for–after all, Jethropolitan’s infrastructure is dwarfed by Warner Bros.–Scott is content in knowing that he’s able to make a kind of music that he never would have been able to make three years ago. A kind of music that truly deserves to be called his kind of music.

“They [the major labels] are getting further and further away from real country music. The blood and guts of real country music…I just don’t really hear it. If properly promoted it could still do real good. There are a lot of people out there who really miss traditional country music. There’s just a disconnect between what the industry thinks and what the people think. I don’t know that a lot of the people at radio know what real country music is. They really don’t give a shit where [the music] comes from, they’re just worried about selling their ads. And I understand that—they’ve got a job to do. But overall it’s hurt our format.”

“You know, it’s such an objective thing. I don’t want to sling mud and talk shit about someone else. It’s not all sour grapes. There’s room for everything. And I’ve got a good base built.”

- Lists13 years ago

Top 10 Country Music Albums of 2010

Interviews5 years ago

Interviews5 years agoJohn Rich – The Interview

Song Reviews16 years ago

Song Reviews16 years agoTaylor Swift – “Love Story”

Interviews5 years ago

Interviews5 years agoHoneyhoney on Hiatus: Revisit our 2008 Interview with Suzanne Santo

Album Reviews14 years ago

Album Reviews14 years agoAlbum Review: Miley Cyrus – Can’t Be Tamed

Song Reviews6 years ago

Song Reviews6 years agoThe Band Perry – “Hip To My Heart”

Columns5 years ago

Columns5 years agoThe Link Between Folk Music’s Past and Present

Columns5 years ago

Columns5 years agoIs Marketing Killing Rock and Roll?