Columns

Is Marketing Killing Rock and Roll?

For some years now, this humble opinionista has found himself deeply alarmed about the increasing weightlessness of rock and roll. As Elvis Costello pleaded more than 30 years ago: Where are the strong? Who are the trusted? Where is the harmony?

The first flowering of my budding obsession with rock and roll came as July melted into August, 1971. From the back seat of my father’s new Cougar convertible, listening to the radio tuned to then-Top 40 station KRTH, I was suddenly overcome with quiet rage. My (then) all-time favorite song—the Raiders’ politically courageous (at least to my pre-adolescent ears) single “Indian Reservation (The Lament of the Cherokee Reservation Indian)”—had just been unceremoniously booted out of its #1 slot by the treacly “How Can You Mend a Broken Heart?,” from those banal Australian schlockmeisters the Bee Gees.

Someday, someone would pay for this. I had had my first taste of bloodlust.

Flash forward eight years or so, and join my Music Critic Origin Story in situ:

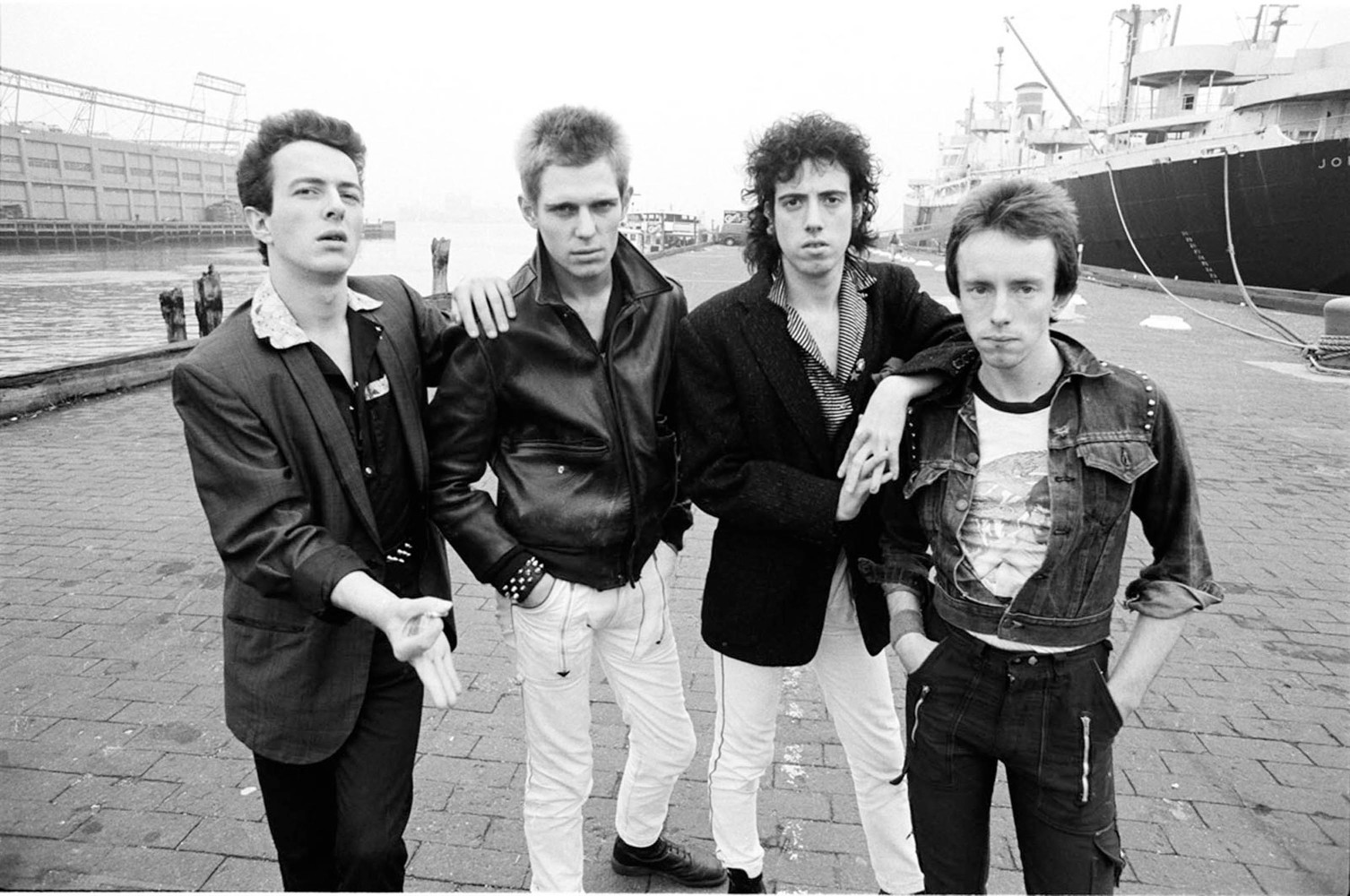

Suffice it to say that from roughly 1979 through the band’s break-up, I was a huge Clash fan. Along with many other true believers, I recognized the band as riding the crest of rock and roll’s fourth (or maybe third) great wave (#1: Elvis; #2: Beatles; #3: Velvet Underground; #4: Pistols/Clash, etc.). Throughout my freshman year at UCLA (1979-80) I commuted from home to Westwood (about 35 miles one-way through L.A.’s worst traffic), playing over and over, on my baby-blue ‘65 VW’s car stereo, a homemade 8-track tape of London Calling.

I had been a passionate rock and roll fan since I was eight or nine, but London Calling revolutionized my sense of music, art and community, and turned me into an evangelist. Two years later, the UCLA Daily Bruin ran a pseudo-hip, half-baked dismissal of Sandinista! that pissed me off. Knowing I could have done better, I strode into the Bruin offices and, on the strength of a test review (of the Go-Go’s’ Beauty and the Beat), began, in Thelonious Monk’s words, dancing about architecture. Within a year, I was the paper’s reviews editor; by graduation I was at the Bruin more often than I was in class.

After graduation, I shifted from one writing/editing job to another, generally having a fabulous time, and always on the prowl for that elusive fifth (or maybe fourth) wave. Since punk broke, the closest rock and roll has come to producing another true prophet is Kurt Cobain. His core vision, however, was of shared pain, which ultimately proved fatally introspective—an artistic and communal cul-de-sac. This is not to say that the mid-80s marked the death of rock and roll (as some critics fatuously claimed back in the day). The Replacements, Los Lobos, Husker Du, the Blasters, the Minutemen, Elvis Costello, XTC, the Meat Puppets, plus about 849 others (including several dozen women, and it was about damn time), brightened up my days and nights.

But unlike the Clash, none of them wanted to be bigger than the Beatles (who in their day, of course, wanted to be bigger than Elvis… who apparently wanted to be bigger than Dean Martin).

In 1991, I started up as a staff writer for the MCA Records publicity department and discovered why the phrase “music industry” is two words long. Fortuitously, at MCA (now Universal) I had landed at just the right vantage point to observe what I have come to believe is the single key moment in post-punk rock and roll history: the genesis of niche marketing.

For nearly 40 years, up until the early 90s, the music industry’s major labels had been famously inept at predicting or recognizing the unprecedented potential (artistic, social and monetary) inherent in rock and roll, the most democratic art form ever created. Examples of industry myopia are legion; the most damning is that nearly every major artist or band, from Elvis to Nirvana, was first signed by a small, independent label, only to be acquired later by a major (Dylan is the big exception).

So, one day in the early 90s (let’s say, just for kicks…August 27, 1992), some nervous junior executive at one of the majors held up his or her hand at a meeting and meekly suggested that maybe instead of slicing the promotional pie into just five or six pieces (pop, rock, R&B, country, jazz, maybe gospel), why not make 15, or 20, or 50 slices—each with its own mini-staff of publicists and promoters? Not just R&B, but Urban Contemporary, Dance, Hip-Hop and Quiet Storm. Not just Rock, but Alternative, Hard Rock, Adult Contemporary, Adult Alternative, AOR, DOR. Then, subdivide even further: Grunge, Thrash Metal, Sadcore, Dream Pop, Skate Punk, Electronica. I could go on and on and on.

Out of the mouths of critics, this kind of musical name-dropping can, at its best, represent an enjoyable game of lexicographic one-upmanship. However, from the offices of the quickly-consolidating majors (and then there were three…), genre ominously morphed into straitjacket. Thirty years ago, a label was judged by how many gold and platinum records it could hang in its lobby. Now, the labels figured that, rather than blow their annual budget on five or six potential platinums, they could squeeze an equal or greater amount of profit out of 50 or 60 tightly pigeonholed niche-marketing campaigns, each moving 50,000 to 200,000 units apiece.

What in God’s name, you ask, does all this have to do with the Clash, fercryinoutloud?

OK, here’s where it gets ugly. Back before the Niche Marketing Era (as I’ve tried to identify it), an 11 or 12 year-old aspiring rock star still had the entire universe spread out before her. Thanks to the general haplessness of the music industry, rock and roll still begrudgingly reserved a chair for the uncategorizable dreamers, the obstinate optimists who just might explode into the Next Big Thing. In the mid-90s, however, the newly minted army of niche marketers began insisting to an entire generation of musicians that unless their music matched one of the specific sub-categories that the label was willing to market, the young-’uns might as well stick to driving trucks.

As a profit-making scheme, niche marketing worked smashingly well for the record companies (although, truth be told, the obscene profits of the 1990s were just as likely fueled by plunging CD manufacturing costs). But—and here’s the truly evil part—after three or four generations of kids having been lectured by record-industry suits that the road to rock and roll immortality lies best within the carefully delineated boundaries of their given marketing niche, that lie became the truth that future generations of punks and punkettes believe. It’s the only option they’re given. And if you can’t realize that there exists the possibility to dream beyond genre, to aim higher than you possibly can reach, to change the world for the better, well… you aim lower and dream smaller. And you don’t even know you’re shrinking.

To quote an unidentified picture caption from the Sandinista! press kit: “The Clash made promises they couldn’t keep, kept promises no-one else could have made, resolutely stuck themselves in the firing line with the singleminded courage of lunatics or children, got knocked down, got up, made fools of themselves, dusted themselves off and carried on.”

I’ve been searching for those qualities in a band, and not finding them, for 25 years.

- Lists13 years ago

Top 10 Country Music Albums of 2010

Interviews5 years ago

Interviews5 years agoJohn Rich – The Interview

Song Reviews16 years ago

Song Reviews16 years agoTaylor Swift – “Love Story”

Interviews5 years ago

Interviews5 years agoHoneyhoney on Hiatus: Revisit our 2008 Interview with Suzanne Santo

Album Reviews14 years ago

Album Reviews14 years agoAlbum Review: Miley Cyrus – Can’t Be Tamed

Song Reviews6 years ago

Song Reviews6 years agoThe Band Perry – “Hip To My Heart”

Columns5 years ago

Columns5 years agoThe Link Between Folk Music’s Past and Present

Interviews5 years ago

Interviews5 years agoCatching up with Chris Hillman of The Byrds & The Desert Rose Band