Columns

A History of NYC Busking and Street Performance

Having spent the first part of my life on an Indian reservation, I was no stranger to legal battles; land rights, water rights, borders and boundaries (where they begin, where they end, and even, “how high does the sky go?”). These early debates whet my appetite to understand and make sense of a legal system that seemed misunderstood and senseless, at best. Since Indian reservations were considered sovereign nations, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights were laws that didn’t apply to me. I was fascinated by the idea of the Founding Fathers—dressed in baggy pantaloons and starchy shirts—etching out the future of a nation with their feather pens. A nation that would surely grow and change and evolve, for better or worse, into something different than it began.

And change, that nation did.

I arrived in New York City in the wake of Barrack Obama’s election to the presidency. Hopes ran high, excitement was contagious, and—according to the president-elect—change was inevitable.

I wanted to experience that change first-hand. I wanted to be in the middle of the Apple, savoring the smells that wafted down the alleyways, hearing foreign tongues dance through the air. I also needed to earn a living.

One day, while wandering through the jungle of Times Square, I came across Benjamin Sherman, who had a company called Practice Safe Policy. Benjamin had married safe sex and politics—two of my favorite topics. I couldn’t wait to hit the streets and sell his line of novelty political condoms. But, there was paperwork to be done, licenses to be issued, forms to file. Once all was in order, I photocopied the regulations defining where and when I could vend political merchandise, packed up my inventory and set up station in Union Square.

I was promptly arrested.

No warning or ticket or summons. Just handcuffed and carted off to jail, where I spent the next eight hours contemplating the error of my ways.

I stayed off the streets until my court date, in which the case was dismissed with the wave of a hand and the flick of a stamp. Feeling a new sense of confidence, I added the copies of my dismissal to my portfolio of documents and went back to the streets. Within twenty minutes, I was approached by the police again. This time, I wasn’t worried. I gave them my (now fatter) folder, knowing full well that this was a miscommunication and I would be conducting free enterprise momentarily.

So, when the officer instructed me to put my hands behind my back and handcuffed me, I demanded an explanation. His words, and I quote: “Just because it was dismissed, doesn’t make it legal.”

After another eight-hour jail stint, I began to more seriously consider what street vendors and performers had been telling me about; being chased by cops, ticketed, fined and imprisoned, and I wondered how free speech and censorship can exist simultaneously.

New York City earned the moniker “the melting pot.” Between 1890 and 1920, 18 million new citizens flooded into her harbor; Jews, Catholics, Irish, Italian, German and Eastern Europeans. They brought their languages, their foods, their art and their dreams of becoming American. As James Truslow Adams said in his 1931 book, The Epic of America, “the dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone, with opportunity for each.”

It was during this time that street performing was elevated to a new level. New York became the backdrop for organ grinders on the sidewalk, accordion players on subway platforms and marching bands on the pavement. She was alive with the flavor of other cultures; teeming with the art of other ethnicities.

A decade later, as the country did its free fall into economic chaos, New York was the center of the decline.

Truth is, people were poor. As a response, many turned to busking as a way to make money. The streets became overrun, space was limited, fights broke out and frustrations mounted. The government responded, citing public safety issues and noise ordinances as reasons to ban busking.

However, what is probably more accurate is that the government did not know how to respond to street performers. Were they beggars, panhandlers, performers or a threat to law and order? And in simply not knowing what to do with them, Mayor La Guardia did what government often does with things and people it doesn’t know what to do with—he outlawed them.

On January 1st, 1936, the artists were officially the criminals.

Despite public outcry, radio and media support for street performers, and judges dismissing cases left and right, the ban stayed in effect for the next 34 years. During FDR’s fireside chats, during the beat movement, during the hippie movement, during Rosa Parks, during Martin Luther King, during the Vietnam War; all these things came and went, but the ban on New York street performing remained.

It wasn’t until 1970, when poet Allen Ginsberg challenged the constitutionality of the ban (and won) that New York City Mayor Lindsay lifted it.

But the controversy was far from over. The ban was only lifted for street performers, not subway singers. The next 20 years saw the courts overflowing with cases from subway singers, mostly being dismissed. In 1989, the New York Transit Authority proposed another ban; this time, singling out musicians on subway platforms. Spontaneous acts of crime such as juggling, poetry reading and folk singing erupted. The Transportation Authority listened, and then did something remarkable: it compromised, officially forbidding only amplification devices on platforms.

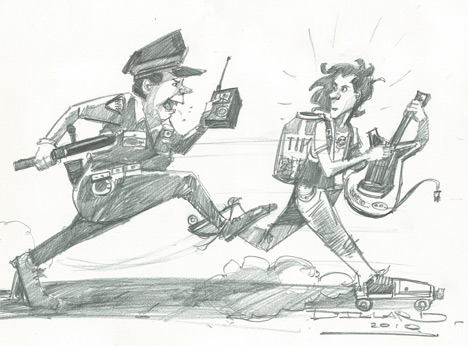

To enforce this legislation, the NYPD would be armed with decibel level readers as well as nightsticks.

As Luke Ryan, the Father Time of underground busking remembers, “the cops had to carry these big decibel readers to make sure we weren’t too loud, which I’m sure they loved—you know, chasing someone down and pulling a decibel reader and then a train would go by. It really didn’t work. It was ridiculous.”

Since the ban still remains in effect today, I am very hopeful of seeing an NYPD Blue chasing down a subway singer with a decibel meter.

But, it was ridiculous, so in 1987, MUNY (Music Under New York) was born. MUNY is a program that allows musicians to legally perform in the subways. They audition, are selected, are given a permit, and then are scheduled. The permits are free and a tax ID stamp is purely discretionary. MUNY is like a modern day Harvey Dent of the underground; a character, who brings about good or evil based on a coin toss; you can’t really love him, you can’t really hate him.

Yet, there are some musicians who stubbornly continue to play without the MUNY blessing. They are aggressively pursued by NYPD and Transit Police. The bureaucracy calls them freelancers; I call them musical pirates. And as I seek them out and chat with them, they speak the same language, share the same points and assert the same propositions. One consistent theme has to do with public space.

Public space is, by definition, an area or place that is open and accessible to all citizens regardless of gender, race, ethnicity, age or socio-economic level. Parks, streets, town squares and subway platforms are considered public spaces; places where the government cannot limit one’s speech beyond what is reasonable, including religious and political free speech.

In New York City, Central Park would be considered a public space. Thoth, one of our featured subway buskers, was arrested there and taken to jail on July 12, 2009, as booing crowds gathered to watch him handcuffed and escorted to a police van. Thoth has been performing in that public space for 12 years.

Union Square is also considered a public space. And even though I had my green folder with the photocopied city ordinance and maps, outlining the parameters of this public space, it was also the space for my first arrest. If you’ve ever watched Friends, one of the opening images is of the amazing Washington Square—another public space.

“Washington Square is a place where people you knew or met congregated every Sunday and it was like a world of music…bongo drums, conga drums, saxophone players, xylophone players, drummers of all nations and nationalities, poets who would rant and rave from the statues. You know, those things don’t happen anymore, but back then, that was what was happening. It was all street.” (Bob Dylan, reminiscing on Fourth Street Revisited.)

As the debate continues unabated, and we all await our next court dates, I realize that Obama and Dylan are both right.

The times, they are a changin’.

- Lists13 years ago

Top 10 Country Music Albums of 2010

Interviews5 years ago

Interviews5 years agoJohn Rich – The Interview

Song Reviews16 years ago

Song Reviews16 years agoTaylor Swift – “Love Story”

Interviews5 years ago

Interviews5 years agoHoneyhoney on Hiatus: Revisit our 2008 Interview with Suzanne Santo

Album Reviews14 years ago

Album Reviews14 years agoAlbum Review: Miley Cyrus – Can’t Be Tamed

Song Reviews6 years ago

Song Reviews6 years agoThe Band Perry – “Hip To My Heart”

Columns5 years ago

Columns5 years agoThe Link Between Folk Music’s Past and Present

Columns5 years ago

Columns5 years agoIs Marketing Killing Rock and Roll?

Pingback: Considering Busking in New York City? Here’s What You Need to Know – Artistic Fuel

Pingback: Considering Busking in New York City? Here’s What You Need to Know - Artistic Fuel