Interviews

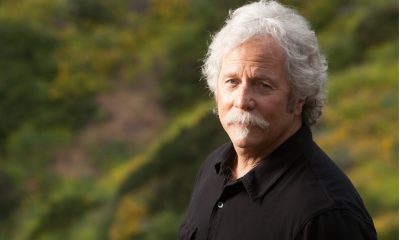

John Rich – The Interview

He’s one of Nashville’s most gifted songwriters, equally adept at penning heart tuggers and barn burners.

John Rich may be contemporary country music’s most enigmatic figure, both a larger-than-life symbol of excess and a purveyor of heartland populism.

Once an unheralded member of the band Lonestar (catch his lead vocals on “Paradise Knife and Gun Club” and “John Doe on a John Deere”), Rich rose to national prominence alongside Big Kenny as one half of Big & Rich.

The duo’s debut album Horse of a Different Color is remembered mostly for spawning the country rap anthem “Save a Horse, Ride a Cowboy,” but a deeper dive turns up gems like “Holy Water,” a striking song about abuse and healing.

Even people who are ruffled by Rich’s big personality or turned off by his constant showmanship will admit that he’s one of Nashville’s most gifted songwriters, equally adept at penning heart tuggers and barn burners.

Still, he may be best known as a TV personality, having appeared on CMT’s Gone Country and NBC’s 2008 reboot of Nashville Star. In 2011 he emerged victorious on the fourth season of Donald Trump’s Celebrity Apprentice.

The one area in which Rich hasn’t yet reached the pinnacle of success is as a solo artist, with 2006′s Underneath the Same Moon peaking at #64 on the country albums chart. Now he’s back with a record titled Son of a Preacher Man and the rousing lead single “Shuttin’ Detroit Down.”

JIM MALEC: John Rich…

JOHN RICH: Jim.

MALEC: How are you doing today, John?

RICH: Good. I just wanted to let you know, before we start, that I read all your reviews on my records and on my stuff, and you’re an interesting commentator to say the least.

MALEC: I appreciate you taking the time to talk to me today, despite those reviews. You know what they say about opinions. I do, honestly, respect your work. It is truly an honor to finally get to talk to you today – the one and only Cowboy Stevie Wonder.

RICH: That’s a fun title to have, yeah. Groovin’ cowboy music, you know.

MALEC: First of all, and I have to ask you this because I’ve always wondered — what in the hell does “Green green grass and a rubber Russian bimbo” mean?

RICH: Well, you’d have to ask Big Kenny. “Green green grass and a rubber Russian bimbo/No one’s got the name for the brain in the scarecrow.” Big Kenny wrote that. So you’d have to ask Kenny – and then you’d probably have to write a novel about whatever it means. I just thought it was a funny lyric and that it was fun to sing. He had a Russian girlfriend at the time, maybe that had something to do with it.

MALEC: Probably. This is totally unrelated to that, but important nonetheless: I have a picture on my office wall of you and Kenny at the 2007 ACM awards – you’re standing there with a bunch of people, including John Legend and the one and only Lil John, who, so the story goes, hung out with you later that night in Vegas. So I have to ask you – is Lil John, in fact, the world’s greatest rapper? And would “J. Money” be willing to work with him on his next project?

RICH: I like Lil John. You know, one thing about me is that I have friends in all genres of music that you would never think I’m friends with. But I’m friends with Lil John and John Legend and some of these guys. Chad Kroger and Kid Rock and just a cross section of people.

Lil John is a big country music fan. He likes the fact that country music talks about the real stuff. And I guess in urban music a lot of the big artists, the reason they’re big is because they talk about what’s real. They talk about their neighborhood and about what they’ve gone through. Country music’s the same thing, just with a different sound around it. It’s the same sentiment. If you’re real, you’re real. And I think that’s why I get along with a lot of these guys. I have respect for them, they have respect for me.

MALEC: You’re talking about things being real, and I do want to congratulate you on the success of “Shuttin’ Detroit Down,” which deals with a very real problem. I do have a question about that song, though. Outside of your outrage over what has transpired with the financial situation, what do you think the best solution is? Because it seems like that song presents a bit of a Catch-22. On one hand, the song criticizes the financial bailout. But on the other, it seems like a failure to bail out the dying auto industry would have amounted to literally shutting Detroit down — which would result in massive job losses for the people the song is supposedly speaking to and about.

RICH: See, the bigger point and the bigger picture of “Shuttin’ Detroit Down” was never meant to be strictly about Detroit. To me, Detroit is Ground Zero of the economic meltdown, and obviously it’s the singularly hardest-hit city in the United States. Without a doubt. But I come from a neighborhood where it’s all generational farmers. Depending on where you’re from in this country you have your own story of what it’s like to work there and what type of work you’re doing.

What made me write the song was the disgust I had over turning on the news every night knowing people in Detroit and everywhere else in the country are losing their jobs and are barely hanging on to their houses while our taxpayer dollars are going to these Wall Street CEOs, who are then spending that money – our money – on jets and remodeling their offices. It’s such a sign of disrespect to me and every other taxpaying American. That’s when I picked up the pen and paper and wrote the song. And I used Detroit as the emblem of hardworking America. The song is not just about Detroit. But I do believe Detroit, since WWII, has represented hardworking America.

If you want to go in and start dissecting why the auto industry is in trouble, man, that’s above my capability to go into that. I mean, unions and all the things that come into play there. Man, it’s way beyond my scope of what I really know factually. But what I do know factually is people are fed up with seeing the people they vote into office give their money, over and over and over again, to people who do nothing but abuse it. That’s what the song is about, and to me that’s why people in Texas and in California, people in Boston and in Florida, why people all over the United States love the song “Shuttin’ Detroit Down.” They’re not from Detroit. They’ve never built a car. That’s not why they like the song. They like the song because the sentiment of the song is an American sentiment right now.

MALEC: I understand that Merle Haggard has talked to you about recording the song. How does that make you feel?

RICH: He came up to me and he said, “Tell me about this song you wrote about Detroit.” He said, “Tell me the lyric.” And so I told him the chorus lyric and he looked at me and said, “Son, that reminds me a whole lot of ‘Okie’.” As in from Muskogee. I guess that’s the highest compliment I’ve ever been paid as a songwriter. Or probably ever will be paid as a songwriter. And then he asked me, “Would you mind if I recorded that on my next record?” I just asked if he was kidding.

I hope he follows through on it. I’d love to hear one of the greatest of all time sing that song.

MALEC: Your next single from Son of a Preacher Man will be “The Good Lord and the Man,” correct?

RICH: That’s the next single. It’s a song I wrote about my grandfather. He was a WWII veteran. He had six purple hearts. In WWII, he lied about his age – he told ‘em he was 18 when he was only 17. He went in a year early and was just one of the greatest men I ever knew. And it dawned on me one day that I couldn’t think of a country song about the greatest generation – the people who literally saved the world. The people that beat Hitler and beat imperial Japan and beat Mussolini. And to me, we’re looking at an American crisis right now in the financial system, but let me tell you that’s nothin’ compared to what they looked at. They were lookin’ at Nazis. You know what I mean? When I sing about him and that generation in this song it gives me a little bit of hope that, hey, if we can do that – if America is capable of winning WWII – we’re capable of getting through this.

MALEC: Who is “The Man” that you’re referring to in that song? Because you don’t seem to be, in other contexts, an especially big fan of government.

RICH: The man in this song is my granddaddy. The man. He was “the man” to me. You know, like if somebody walks up and says, “Jim, you’re the man.” My Granddaddy, he was the man. And also, when I say “the man” in that song it refers to all the men and women that fight. It’s not the government, it’s our fighting men and women. But for me, on the singer level, it was my Granddaddy Rich.

MALEC: Let’s put politics aside for a minute. As one of the most successful songwriters of our generation, how do you go about balancing artistic and commercial concerns?

RICH: I’ve written some songs that were strictly commercial, you know, maybe if I’m trying to write a song that would be great for a tour like “Comin’ to Your City” or something like that. But even there, you can chop that song up and see there’s a lot of colorful things going on in there that are pretty artistic.

A song like “Shuttin’ Detroit Down,” for instance, is such a personal message from me, and a real serious sentiment of a song. If I sing it for you on an acoustic guitar it would hit you differently that it hits you when you hear the recording. When I sing it on a guitar, people say it sounds like a Woody Guthrie song. Which is a huge compliment. But when you hear the recording of it, you hear that I produced it with more of a commercial edge on it, because it’s a real serious subject and I didn’t want people feelin’ bummed-out when they heard it. I wanted them to feel like going, “Hell yeah, John! Tell ‘em about it!” So I put a little more energy in that track.

So I’d say I find the balance there. That’s why I like to produce my own records, because I know in my head where I want to take it.

MALEC: I want to ask you about Nashville Star. When you were promoting Nashville Star, you made some comments that were critical of American Idol. Later, you went on the criticize Nashville Star itself. I have nothing to ask about those comments in particular, but what I do wonder is whether you think these types of TV competitions help or hurt country music?

RICH: If Nashville Star had been handled correctly it would have been a huge boost for country music. But instead you had people at NBC who didn’t know their head from their ass about country music, and they made decisions on their own and without…

My opinion meant nothing. Jeffrey Steele’s opinion meant nothing. Jewel’s opinion meant nothing. And we’re the people actually living in Nashville, making country music for millions and millions and millions of people. We are country music fans. I am a country music fan. I know what I love about it.

Country music doesn’t have to be made cool. Country music is cool. Country music is the biggest format out there. We sell out stadiums every single year. So when NBC went about it the way they did, it was, in my opinion, embarrassing. And really not an accurate representation of what country music is all about, and what our fan base is all about. And that’s where my frustration came from.

MALEC: Thanks for your candor on that–

RICH: –That’s pretty clear, isn’t it?

MALEC: Very clear. What drives John Rich? Does he crave superstardom? Money? Creative acclaim? All of the above? What is it that gets you up in the morning? What is it that makes you be the go-getter that you are, John?

RICH: I grew up in a place called the Tierra Grande Trailer Park. It was on the west side of Amarillo, Texas. Going to the food bank every month was a common occurrence in my family. There were four kids and my dad was a small-time preacher who also sold cars on the side to make enough to actually pay the bills. I never went to college, but I started listening to country radio when I was five year old, on my little radio in the bedroom there. My dad taught me a few chords on the guitar and I took it from there.

Country music has given me every great thing I’ve ever had in my life. The country music fans have stuck with me through many incarnations of my career, from Lonestar to Big & Rich to now on this solo record I’m doing. So why in the world would I want to take a vacation from what I’m doing right now? Yeah, sometimes I might work too hard in some people’s opinion, but I figure I have just a certain amount of days to what I love to do, which is make country music on this level. You know, you’re not gonna be young forever and have the energy to do it, and frankly people aren’t going to give a damn about you forever–unless you’re lucky like George Strait or someone like that, and I don’t think there’s a great chance of that happening.

So I’m gonna write as many songs as I can, and do as many shows as I can, and promote country music as much as I possibly can while I have the opportunity. That’s what gets me up every morning. I just want to give back all the great things the fans have given me.

JM: Thanks John. I appreciate your candor and, once again, for taking the time to talk with me. I’ve really enjoyed it. Like I said earlier, I do respect your work a great deal. I may hold your feet to the fire, but I hold everyone’s feet to the fire.

JR: I like most of the things you write. And then sometimes I’ve got to read it two or three times to make sure you’re not being a smart ass. But that’s alright. You’re a very creative writer. I like reading what you write, even though sometimes I go, “Aw, man, come on!” But you’re a talented writer and that’s why I keep up with your reviews.

- Lists13 years ago

Top 10 Country Music Albums of 2010

Song Reviews16 years ago

Song Reviews16 years agoTaylor Swift – “Love Story”

Interviews5 years ago

Interviews5 years agoHoneyhoney on Hiatus: Revisit our 2008 Interview with Suzanne Santo

Album Reviews14 years ago

Album Reviews14 years agoAlbum Review: Miley Cyrus – Can’t Be Tamed

Song Reviews6 years ago

Song Reviews6 years agoThe Band Perry – “Hip To My Heart”

Columns5 years ago

Columns5 years agoThe Link Between Folk Music’s Past and Present

Columns5 years ago

Columns5 years agoIs Marketing Killing Rock and Roll?

Interviews5 years ago

Interviews5 years agoCatching up with Chris Hillman of The Byrds & The Desert Rose Band